Haunted, Philadelphia, USA

I grew up in a war-torn country in the Middle East, ruled by a dictator. I always thought I intuitively understood what the phrase “life is unbearable” meant and felt since that was my lived reality for more than two decades. I lost immediate family members and was displaced because of oppression. However, the violence and horror I experienced pale in comparison to the genocide unfolding in Gaza. I’m haunted by this phrase I saw posted on FB “Imagine they are living a life you cannot bear to watch.” Objectively, I have a fulfilling life right now in the US, but I am haunted by the knowledge there is horror in the world right now (Sudan, Haiti, Congo, Afghanistan in addition to Palestine) that I cannot bear to watch because of the scale of its gravity.

Haunted

AR:

Your letter is so deeply urgent & simultaneously so very difficult to answer because the tragedies you are describing are very much ongoing, occurring in the most present tense, in real time—even as I write these words, incomprehensible acts of violence, destruction & displacement reign supreme in so many corners of our world. The pain is too great to bear & the earth is oversaturated with the blood of the innocent. What can we do but cry out in all our anguish from the depths of our consciences until our voices shatter the ivory towers surrounding us and our collective tears form raging rivers—a deluge of grief pouring through the open streets. & even this is not enough.

In a recent poem of mine entitled “after Arendt” I begin to attempt to think through the paradoxical paradigm built into the banality of evil we inhabit:

after Arendt

a double catastrophe by proxy:

destruction of the human

life, by destruction of the

human mind, both

thru loss of common sense,

which comes first?

I wonder: have we lost all common sense for good? Where are the catastrophic winds of this prolonged contemporal moment blowing us? Will they finally blow us over? How can we brace ourselves, & with what?

Another recent poem of mine responds:

poem in reply to a letter

east bay early

dawn sky over hill

sweet dream-like

upward breath

from which I long

never to wake up

to the nightmare

waiting at my gate

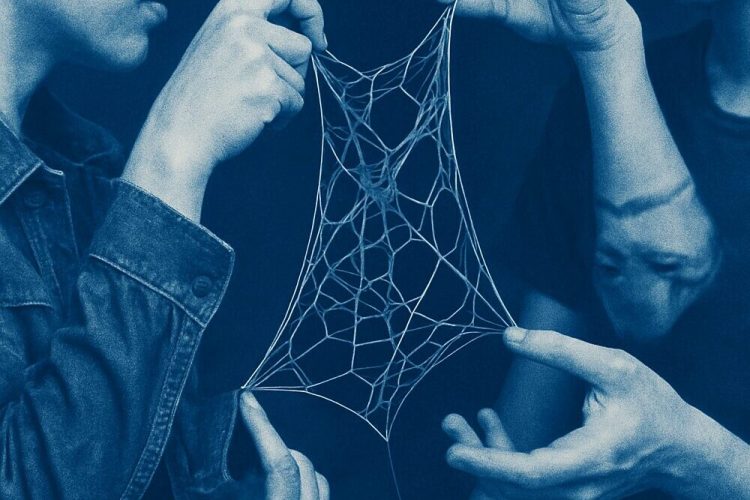

heartsick & sleepless

unraveling—en

tangling my

deepest roots

outside the dead

lie naked &

graveless from

rd to rd, while

the living blunder

on, cope in every

sense & senseless

manner under the

sun, & under

the sheer toxic

weight of it all

look to sky

at mornings

first yawn

dream moment

by moment

into respite—

We search for words & words continuously fail us. Yet the search for words—for a response, for the ability to respond in whatever way possible—is crucial & worthwhile in and of itself. “Not every person is a prophet,” writes the poet Avot Yeshurun, “but every person is a poet. Because poetry obliges that a person respond to everything.” This, I think, is what Jerome Rothenberg means when he writes that “after auschwitz / there is only poetry.”

I want to conclude this reply with the final lines from a recent essay of mine on translation in the face of disaster:

it is not our story therefore that must be told. it is the other story that cannot not be. it is the nostory not told that cannot be. the untellable story none tells, as Paul Celan writes: “No one bears witness for the witness.”

that is, none enunciates, emaciates, is pronounced dead, then buried in language — as “dead” language or culture — understood as anonymous, anomalous. buried in the word, still breathing tho silent. the screams of silenced peoples (silenced by the silent), people forced into silence, people murdered en masse without a chance to survive — thrown off ships, or starved; slaughtered in oceans, forests, cities, fields, factories — the screams which end in utter silence rising up from the catastrophic fallout of the very contemporary air we breathe.

not only because these facts have changed and poisoned the very air we breathe, not only because they now inhabit our dreams at night and permeate our thoughts during the day — but also because they have become the basic experience and the basic misery of our times. Only from this foundation, on which a new knowledge of humans will rest, can our new insights, our new memories, our new deeds, take their point of departure.

—Hannah Arendt

what’s a poem? air.

—Avot Yeshurun