N., Bay Area, CA, United States

Hello dear poet(s), A privileged visit to the Great “dismal” Swamp has stirred incredible tension in me. Alongside disagreement with its untrue place-name, are connections of attitudes towards wetlands and their rich ecologies (mosquitos included) to larger systems of disposability. This swamps, once useless to colonists, became refuge to Indigenous people and African maroons. I have been wondering how to reconcile nature as escape….not as movement towards desensitization of everyday violence, but towards recognition of radical possibility. `

Sincerely, N.

SB

Dear N,

The winter tidings I write you with meet me here, by my snowy desk-side window, struck by the idea that your answer lies snuggled within your question like a cat curled up by a firelit hearth.

You ask: “[H]ow to reconcile nature as escape…not as movement towards desensitization of everyday violence, but towards recognition of radical possibility.”

My response: Don’t. Don’t reconcile, deepen. Deepen…

Perhaps that idea of *escape* is itself a remnant of coloniality. What if, instead, we consider, phenomenologically, escape and nature as *to* rather than *from* and reconcile nature to radical possibility instead through engagement.

You already know, N., what’s there, its history, even from your “privileged” space. So, what you have now is opportunity. You can choose to live *in relationship* with that history; even further, you can choose to live *in relationship* with the contemporary and ongoing reimagining and remaking that the ecologies offer.

Ecology, even—shudder—the mosquitos, as you note, provides a good eye chart here because you rightly suggest that the nomenclature gets us lost. Ecology names the collectivity of survival. At minimum, we focus on “dismal” while eliding “great.” We walk right by wetland, and holding ground, and root-dark bog, but okay. Okay. Swamp. Let’s let it stand alone in its sibilance.

Swamp.

Re-creation.

Swamp carries the name dismal how a body carries an old bruise. Under green hush, where history rises through mud, new tomorrows form its fog, its frost, its lowing sound of frog. Boggy evidence of who swung the first blow.

Colonists called Swamp useless because it refused their variety of order. Trees: tangled. Water: stubborn as my father. Mosquitos: far too honest about their hunger to folks so dishonest about theirs.

N, you asked about how to reconcile nature as escape without numbness. Look again. See how desensitization comes from distance; how radical possibility rises from immersion. Look again and let the air sting.

Swamp gives no easy peace. Swamp gives mirror knowledge. Swamp gives permission to imagine life beyond the reach of the blade. Molten and alive, Swamp works to sharpen rather than numb. Swamp makes a world which such violent, colonialist minds can’t quite map, a world whose wet shadows remember what fled into her arms, a world whose waters teach us how refusal can grow her own architecture.

If gift is offering, and blessing is condition then, well, what a blessing. How safe (enough) one might find oneself within its wet insistence.

And if escape still feels important, imagine an escape from coloniality itself through accountable action. Imagine escape as a verb you can enter with your whole self.

How might you—in the way that only you can—tap into our histories of maroonage, of fugitivity, and turn that tap toward futurity? What spaces of safety and freedom can you work with nature to create—not just for privilege, not even for self, but for others (the collective self, perhaps, or “us all”)?

Another piece of coloniality that we can get snagged by is its veneration of individuality. Even within our considerations of maroonage, our boots can get stuck in the individual maroon and miss the larger implications of maroonage as community response. As reckoning. As a call-back and reaching toward freedom as way of being, rather than as individual escape.

Within the swamp, experience became and becomes so much more than just tragedy: it became and becomes strategy. We get to honor that. We get to continue its work.

To live phenomenologically in the swamp means to trust sensation and intuition. To learn to the pore: the feel of safe(ish) ground; to the drum: the sound of quiet threat; to the tongue: the subtle grammar of water and reeds, the ululation of predation. Swamp insists that knowledge arrives through the body first, which of course, is a precondition to any human future at all.

Swamp doesn’t promise anyone’s tomorrow; it trains us to stay alive long enough to imagine one. To create and recreate. That’s a radical redefinition of the future as capacity, rather than destination. Survival as adaptation, as refusal of external extinction narratives.

I must extend my loamiest gratitude to my sister, Nana Fofie Amina Bashir, cultural organizer, facilitator, and Southern practitioner of expressive arts & somatic therapies, for being in such fruitful conversation with me about your question. Because, again, Swamp means we are never, ever, alone. To that end, I share with you a few poems that offer, rather than escape, training. A poetic workshop, perhaps, with love:

“The Niagara River,” by Kay Ryan

“Obligations 2,” by Layli Long Solider

“For My People,” by Margaret Walker

“the killing of trees,” by Lucille Clifton

“won’t you celebrate with me,” by Lucille Clifton

“The Rings Around Her Planet,” by Esther Belin

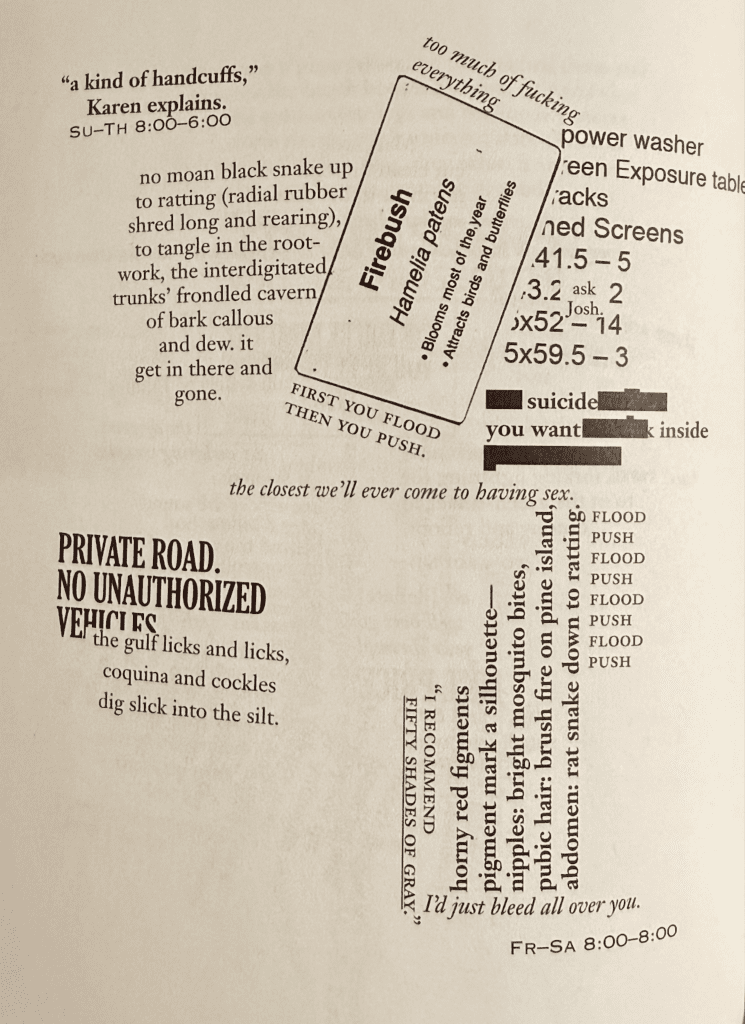

from “No Wake/Too Much of Fucking Everything,” by Douglas Kearney

“Interstate 81,” by Ruth Ellen Kocher

won’t you celebrate with me

by Lucille Clifton

won’t you celebrate with me

what I have shaped into

a kind of life? i had no model.

born in babylon

born nonwhite and woman

what did i see to be except myself?

i made it up

here on this bridge between

starshine and clay,

my one hand holding tight

my other hand; come celebrate

with me that everyday

something has tried to kill me

and has failed.

The Rings Around Her Planet

by Esther Belin

I dreamed of Sappho of Lesvos and she was driving a Hummer, I cannot remember the color but it was parked very close to my minivan. I saw her talking with men from the naval base in Alameda, California. I asked her if she could move hr Hummer and instead she gave me the keys. I drove around the lot until I found the perfect spot next to a brightly painted school bus with the question “Is your world represented to the media?” painted across it in bold red paint. Handing her back the keys, I noticed her skin was a gentle, glowing bronze, not at all the milky white color depicted in her portraits. Her hair was dark and bundled behind her skull, the perfect oval or the capital letter “O,” symmetrical and fluid like her conversation. She wore jewelry made of shells and fastened with leather, reminiscent of the Yurok tribe in northern California who wear dentalium shells with abalone and intricate basket weavings. She was smoking a cigar while talking to me about the war and hand-to-hand combat. I know the men had no idea who she was. I wanted to show her a book of her published writing so she could fill in the blanks. She said she had no time, that she was running out of ___________, that a _________ person was meeting her at the __________ at 4:15 pm.

excerpt from “No Wake/Too Much of Fucking Everything,” Douglas Kearney

Interstate 81

by Ruth Ellen Kocher.

The projects were a gift to us,

the meek who inherit the earth.

Walls for our roaches. Foundations

for our rats. The green paneling

layered like green grown

In a country meadow we never

saw. Sometimes, over

the sound of sex above my head,

I could hear a distant highway,

cars cutting through air

as though no boundaries existed

between there and here.

You must understand thus, the hollow

tunnel of sound-less-ness echoed in movement,

the suggestion of space without walls,

a road that went somewhere

in a heaved sigh of relief.

The Niagara River

by Kay Ryan

As though

the river were

a floor, we position

our table and chairs

upon it, eat, and

have conversation.

As it moves along,

we notice—as

calmly as though

dining room paintings

were being replaced—

the changing scenes

along the shore. We

do know, we do

know this is the

Niagara River, but

it is hard to remember

what that means.