Anonymous, USA

I’m living with a radical reshuffling. Deep familiars, from birth to my mid-century, dead too soon. What if every question begins and ends with grief? Not literally, of course—we require verbs ‘can grief? will grief? is grief? how does grief? why won’t grief?’ And prepositions ‘with grief, through grief, beyond grief, around grief, under grief’. But grief seems to control temporality these days: I no longer know before and after. I am altered. Grief alters. Period. There is a dullness to that end stop. Where does creative possibility live in the grammar of loss?

Anonymous

AR:

Your letter cuts to the very core of something I think about constantly. We are living collectively through an epoch of catastrophe—an era of ongoing disaster—which overwhelms the capacity of human grief as we know it. The vast darkness surrounding us is continuous & all encompassing, & the cracks that let the light in—thinking of the late great Leonard Cohen—are few & far between. Yet, as the eighteenth-century Hasidic mystic, Reb Nahman of Breslov teaches:

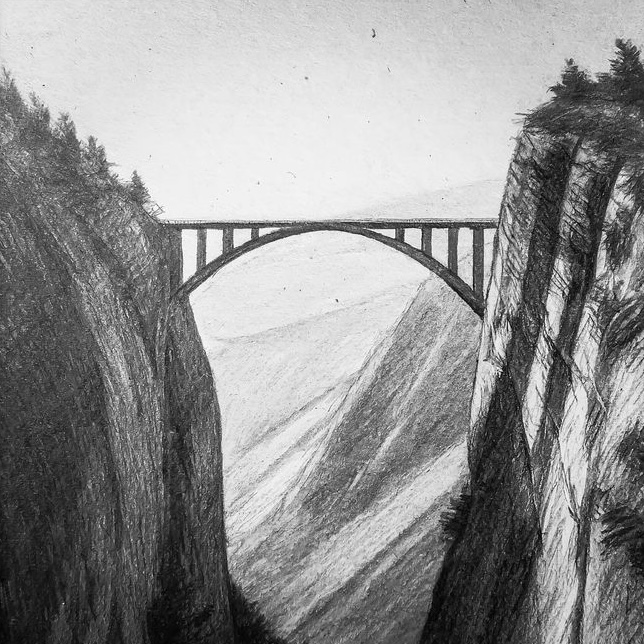

the whole entire world

is a very narrow bridge

& the most essential thing

is not to make yourself afraid

We walk that narrow bridge every day, every hour, feeling it rock & sway beneath us, undulating with the fierce winds of time & change. Our footing ever unsure, our lives are split between the multiplex safety nets & structures we’ve set in place to protect ourselves, & the powerful & paradoxical flux of uncertainty—what the Martiniquan philosopher Édouard Glissant calls the chaos-world: a raw reality that cannot in fact be structured or systematized in any sense.

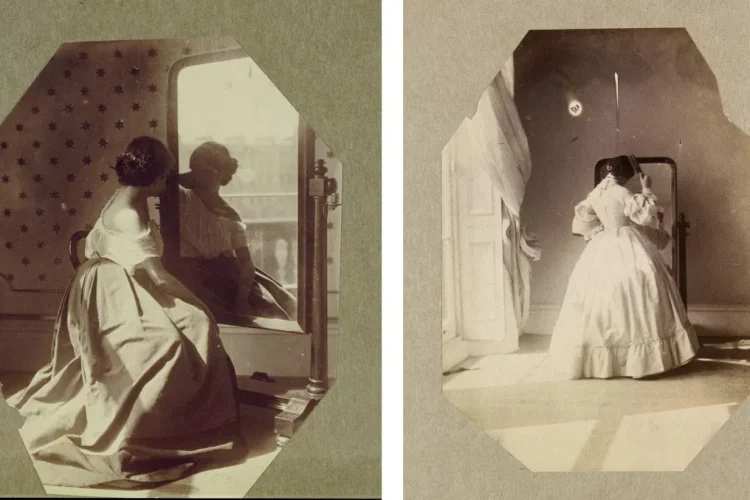

Elsewhere, Reb Nahman teaches that the highest form of joy is in fact joy held together with grief, since sorrow is always just on the other side of joy, its mirror opposite. So it’s not a problem to be grief-stricken—on the contrary, only through admitting our grief can we begin to search out the potential for true joy. But we cannot freeze upon the narrow bridge in self-constructed fear at the prospect of falling—petrified by that feeling of inevitable loss—& must instead move somehow with our sadness through a speculative process called hope. Hope is the profound suspension of uncertainty & doubt, the spectral lifeforce our ancestors have planted within us, & the greatest gift the ghosts give us.

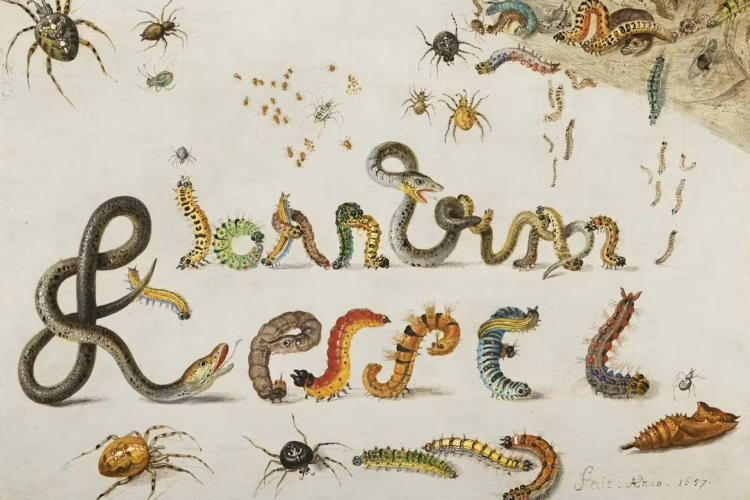

With hope, we can begin to re/generate presence from absence, joy from grief, sacred meaning from banal meaninglessness. Poetry & art might be understood as radical modalities, or channels—in the poet Jack Spicer’s sense—for this spectral lifeforce, & here I am thinking of Primo Levi teaching his friend Jean the Ulysses Canto from Dante’s Inferno during the depths of their imprisonment in Auschwitz; or else, the words of the great Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish: “& I say to myself, a moon will rise from my darkness.”

With solidary regards,

xoAR